Gattaca: Rethinking what ‘dystopian’ means

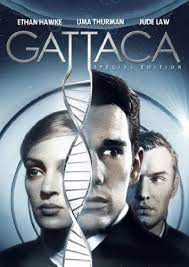

Gattaca

Like most teenagers, I went through a dystopian phase. I read “The Hunger Games,” “Divergent,” and “The Maze Runner” successively, falling in love with dystopia until I abruptly didn’t. The plots suddenly felt repetitive, the characters uninteresting, and my phase was officially over. I returned the books to the library and stopped reading dystopia- that was when I watched Gattaca for the first time.

Released in 1997, Gattaca is a sci-fi/drama movie about the ramifications of being ‘imperfect’ in a ‘perfect’ society. In this world, prenatal genetic modification is the norm, those who undergo it are called ‘valid’ while those who don’t are ‘in-valid.’ Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke) is an ‘in-valid’ working as a janitor in the Gattaca Aerospace Corporation who dreams of going to space- a job reserved for the ‘valid’. With help from German (Tony Shaloub), Vincent finds Jerome Eugene Morrow (Jude Law) a paralyzed ‘valid’ willing to let Vincent take his identity. Now believed to be ‘valid’, Vicent is able to enter the Gattaca training program, and gets the opportunity to go into space. When an administrator of Gattaca is murdered shortly before his launch, and his eye-lashes are found at the scene, Vincent must fight to stay hidden and prove his innocence.

According to Miriam-Webster, the definition of dystopia is: “an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives.” So although Gattaca is not set in a society plagued by atomic wars or bloodsport, it is dystopic. In the world of Gattaca, the ‘in-valids’ and the ‘valids’ who are no longer ‘perfect’ are dehumanized, and barely considered people. They are pushed to the periphery of society, there to provide services for the ‘valid’ but denied the same opportunities. Those in charge substantiate the social hierarchy by claiming that the ‘valids’ are inherently better than the ‘in-valids’ and that the stratification benefits society. The manipulation of what ‘perfection’ means, and the ramifications of not fitting that definition creates a dystopian world-a world where no one is truly free. Both Jerome and Vincent are constrained by this definition, but in vastly different ways.

Jerome’s genetics were programmed to make him an ideal swimmer; he went through most of his life being the best without having to try. We can see that his adult life is lonely, and while it isn’t mentioned explicitly, it can be implied he was ostracized because of his paralysis. Spoiler– we later find out that Jerome purposefully threw himself in front of the car because he was tired of the standard he was held to- spoiler ends. As for Vincent, he spends his life being compared to his brother Anton’s (Loren Dean) who was modified. Anton is the one who gets their father’s name, and the one their parents see a future for. The commonality of eugenics turns families against one another, and makes everything competitive. You can’t just be good, you have to be better, you have to be the best.

The beauty of Vincent impersonating Jerome is that the actors look nothing alike. As customary in their world, when entering buildings, people give DNA samples to prove their ‘valid’ status. The guards who read the results of the test look at Vincent’s face and the photo ID and let him through. They don’t care that there are obvious inconsistencies with his appearance, they just care that the computer system recognizes him as ‘valid.’ Gattaca shows us a terrifying world that is simultaneously full of apathy and rigidity. Where one must meet the requirements, but no questions are asked of those who belong.

The disturbing nature of Gattaca is highlighted by the filmmaking (with director Andrew Niccol and cinematographer Sławomir Idziak). Dark and shadowed colors are used throughout the film, and the score (composed by Michael Nyman) gives the movie a feeling of constant tension. All interactions teeter on a knife’s edge, and the audience is left to wait and see. The audience wants the charade to end, but also wants Vincent to succeed, to prove that there’s no difference between the ‘valids’ and ‘invalids.’

Gattaca uses a technologically advanced world to highlight subvert modern expectations of the dystopian genre, making itself an individual and thought-provoking movie. With a solid cast of sympathetic characters, Gattaca hooks the audience and keeps them in suspense until the last moments. Gattaca is the kind of dystopia I wish I had run into earlier, and the kind I look forward to reading and watching in the future.

9.2/10 would prove Gattaca wrong again

Further breakdown:

Writing Quality: 9/10 Enjoyability: 9/10

Pace: 9/10 Visual elements: 9.5/10

Plot development: 8/10 Insightfulness: 8/10

Characters: 10/10

Additional content:

All of these use a seemingly utopian world to expose something darker underneath

“The Giver” by Lois Lowry: A classic YA novel about Jonas, a young boy chosen to inherit the memories of his society who begins to find fault in his world.

“1984” by George Orwell: Everything and everyone is regulated by Big Brother, an all knowing force who wants to keep everyone safe, by outlawing any thought that might cause a disruption.