Best Books of April

In the wake of the newspaper’s state conference, impending exams, increased classwork, and the resultant burnout, I have had little time and energy for myself. In the midst of this, reading became my rare quiet moment and so I threw myself into it wholeheartedly. Generally, April was a good month for reading. I largely enjoyed what I consumed in addition to reading a wide range of stories– both new finds and returning to books I’d read years prior. I will again include a brief plot description, review, and summary. These books are ranked from ‘wow’ to ‘this is why I read.’

- “She Said: Breaking the sexual harassment story that helped ignite a movement” by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey

In the mid 2010s, New York Times journalists Kantor and Twohey both found themselves investigating the treatment of women in the workplace. For Twohey, this manifested as a report on the numerous abuses of then-candidate for president Donald Trump, and for Kantor, this involved hearing rumors about abuses taking place in the Miramax film company. In the wake of Trump’s election and Twohey’s return to a full-time job post-maternity leave, the pair teamed up to further investigate the film studio and its head Harvey Weinstein. This book is the summary of their investigative efforts and details the process of trying to uncover years of systemic abuse and cover-ups.

Admittedly, I did watch the movie first, but that by no means detracted from the book. Kantor and Twohey are a formidable pair. Their shared work not only shows the strength of their writing, but their relentlessness in trying to right the wrongs of a powerful man and a corrupt system. It is a deeply uncomfortable book to read, and one that gives the audience space to sit with and consider the larger implication of the survivor’s testimony. The team effectively establishes a sense of scale by both showing how the women interviewed for the story represent problems within their field, and by showing how their experiences reflect larger, undealt with structures of power and control. It’s a rallying cry for change, and a nuanced look at the complexities of trauma and standing up in the face of dismissal.

9/10 would bear witness again

- “The Liberal Hour: Washington and the Politics of Change in the 1960s” by G. Calvin Mackenzie and Robert Weisbrot

Iconography and memory remember the 1960s and early 1970s as a period of rapid social change and progress. In “The Liberal Hour” Mackenzie and Weisbrot trace the origins of this movement and its results by establishing greater context for the time and the political forces at play. In addition to highlighting well-known figures from the time, like John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, Mackenzie and Weisbrot give focus to the time’s grassroots campaigns and the overarching trends in the social climate to create a richer picture of the time.

The politics of this era have always been an interest of mine, and finding a book to not definitively but accurately summarize the powers at play was exciting and engaging. By showing the range of movements and individuals who dominated the 60s political space, they are able to better represent the overlooked masses and their role in creating lasting progress in the US. Yet, while there’s unavoidable nostalgia in the reflection of any prior time, “The Liberal Hour,” avoids sentimentality or idolization of what’s gone. This isn’t unexamined praise of heroic politicians, it is a well-considered look at a snapshot in history. By doing this, the people described are allowed their virtues and their flaws, and the liberalism of the time is critiqued for its shortcomings. It is nuanced, well-researched, and moving.

9.5/10 would dive into the politics of the past again

- “Twelve Angry Men” by Reginald Rose

This play, published in 1954, is an intense, one-room drama that chronicles the jury deliberation after testimony for a murder trial is heard. Their decision decides whether the accused will be released or sentenced to death. The trial concerns a young boy (usually 14-16 in most presentations) who has been accused of murdering his father. Eleven of the 12 jurors are convinced of the boy’s guilt, but one, Juror #8, holds firm in his belief that the boy is innocent– or at least that his fate cannot be decided until after a thorough review and consideration of the evidence. The further into their examination they get, the more prevalent the jurors’ biases become, and the blurrier the line of guilt and innocence becomes.

The best reference point I have for Rose’s work is the courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder, which features Jimmy Stewart as the lawyer for a man accused of murder. The actual details of the cases in these two stories differ wildly, but the skin-crawling, pervasive tension is found in both of them. “Twelve Angry Men” does not give its audience the relief found in a murder mystery story– no murderer is revealed nor is a clean explanation of the crime given. Rather, the audience finds themselves drawn into the web of conflicting accounts, uncertain evidence, and personal prejudice that the jurors themselves are privy to. This not only keeps the reader (in my case, but I can only imagine the power of watching this be performed live) heavily invested in the story, but also forces them to undergo the brutal self-examination that the defendant is put through and the jurors embark on. There’s no room for uncertainty in a trial like this, and yet Rose paints a vague picture of overlapping human interests and the fallibility of the human conscience and logic.

10/10 would examine all my biases again

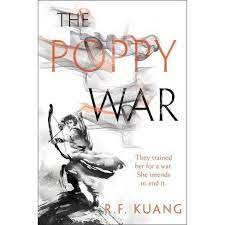

- “The Poppy War” by R.F. Kuang

A fantasy novel of both self-discovery and national identity, “The Poppy War” takes inspiration from Chinese history and folklore to tell the story of war-orphan Rin. Rin, raised in a poor southern province, beats the odds of a corrupted system to attend the most prestigious academy in the continent. As her time at school progresses, tensions rise with the empire’s oldest enemy, and divine magic begins to influence Rin’s life. When she makes a startling revelation about her origins, Rin abruptly finds herself a valuable pawn to the empire in the emerging war. Struggling to understand herself, Rin must set aside the unanswered question in order to survive her changing world.

I first read “The Poppy War” in seventh grade when it initially came out. Admittedly, I was much too young for the book at the time, both in terms of content and appreciation, but I was in-love with it nonetheless and waited anxiously for the other two books to come out. Five years later, I decided I’d had both enough time and distance to reexamine Kuang’s work and was equally enamored with it this time. “The Poppy war” is a perfect blend of external and internal conflict, focusing both on the strain and consequence of violence and the inner-turmoil of feeling disconnected from oneself. Rin is a deeply complex and often unlikeable character, but undeniably compelling and magnetic. Rin’s journey pulls deeply on the heartstrings as she navigates her own identity both separate from and connected to her country and status as a soldier. It is a story of idols and gods, men and war, sovereignty and colonialism, and the complicated struggle between ideals and solutions. It’s often grisly and deeply uncomfortable, and it doesn’t let go until well after the final page.

10/10 would follow a complex antiheroine again

Content warning: While I do love this book, its frank depictions of war and wartime tactics may be upsetting. Use discretion.